Remembering the dust from which I came

Because I'm tired of the same old narrative of women hating their bodies

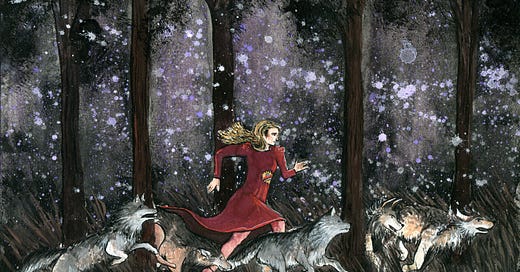

“Women Who Run With the Wolves” by Erin Darling / Darling Illustrations

In Dr. Clarissa Pinkola Estes’ internationally-renowned feminine manifesto Women Who Run With the Wolves, she writes of being taken aback with how wolves hit their bodies together when they run and play. For young pups, play is a full-contact sport, stalking and pouncing on one another in joyful games of tag, or crouching down in stillness before leaping up in a fit of “zoomies,” where they run ‘round and ‘round in circles in a breathtaking wild blur of speed and spinning fur before collapsing, exhausted and happy. Wolves of all ages have been seen engaging in play with their whole bodies, wrestling and tackling, bowing to one another to keep the game going or impishly pawing at another’s face to force him to let go during a game of tug-of-war. Their whole lives are lived voraciously through their bodies – not in spite of them.

Dr. Estes writes that the body is “a multilingual being,” a living record that speaks of temperature and pain and arousal and love and hunger and memory. “To confine the beauty and value of the body to anything less than this magnificence,” then, “is to force [it] to live without its rightful spirit, its rightful form, its right to exultation. To be thought ugly or unacceptable because one’s beauty is outside the current fashion is deeply wounding to the natural joy that belongs to the wild nature.”

There is, after all, no wrong way to have a body. An ancient and beautiful story tells us that in the beginning, there was nothingness, and in the beginning, God said to one another, “Let us make humans in our image.” And then God envisioned and imagined and created bodies. There were bodies with skin the color of clay and the color of fresh milk and the color of rose petals and the color of an inky midnight sky. There were bodies with dimpled buttocks and doughy bellies; bodies with taut thighs and bulging biceps; bodies with angled cheekbones and jutting ribs. There were bodies that loved women and bodies that loved men and bodies that loved both and bodies that loved neither. There were bodies with extra chromosomes, and bodies with missing limbs, and bodies with two seeing eyes; or maybe one or maybe none. There were bodies tall as tree trunks and bodies short and squat like mushrooms. There were bodies that felt at home being female, and bodies that felt at home being male, and some bodies felt at home being both, or neither, or somewhere in between. There were bodies with eyes like rich cocoa and icy glaciers and deep forests, bodies with hair like fine straw and bodies with hair like the swell of a wave, and bodies with lots of hair and bodies with very little.

And God saw them all, and God declared them very, very good.

In her book, Dr. Estes recalls her homegoing to the Isthmus of Tehuantepec in Mexico, the land of her ancestral lineage. She met some of the people whose bloodline she shared, strong and large women who reminded her that females are La Tierra, made to be round and full just like the earth herself. She recounts hearing of a similar voyage her friend Opalanga took to her ancestral homeland the Gambia, in West Africa. There, too, she met some of the people whose bloodline she shared, tall and slender women, who had splits between their front teeth just like did, who reminded her that the space means “opening of God” and is understood in the tribe to be a sign of wisdom.

Perhaps, then, it is possible that every body is good, and beautiful, and purposeful, and wild, and maybe the parts we pick apart and fuss over only need to be reimagined. Maybe we simply need to hear the story of our ancestors again and remember.

My own body is as hearty as the Scottish Highlands that have housed my bloodline for nearly a dozen generations, but also soft in places, just as the fertile farmlands of Madeira and western Asturias, where many others in my lineage have called home. My fleshy hips are wide like the seven hills of Lothian, lined with silvery stretch marks curved like the uisges of the land that birthed my mother. My dark eyes fleck in the sunlight, the same color as the Barbary stag found in the Atlas mountains of North Africa, where my patrilineage courses through like valleys between the clefts.

Most notable are my legs, sturdy and broad, resembling those of my nomadic Berber ancestors, who wandered the deserts of Morocco, and the Scottish travelers in my heritage who would roam the lowlands. For these ancestors, their bodies were what ensured their survival. Strong legs meant they’d live to see another day.

My body cannot be separated from the lands which I came from, the earth that has soaked up the blood and sweat of all my tribes. None of ours can. We are maps of all who have lived before us, chapters in a story begun to be written before the sands of time knew our names. Our bodies bear witness to their struggles and triumphs, their sorrows and pain, the songs they’d sing so quietly under their breaths that no one would hear them, the dreams they dared to conjure up when no one else was around. We are tattooed with their memories, names of our people who once lived with the land instead of on it.

Perhaps, if you’d only quiet yourself for a moment, you might remember.

The thump of your heartbeat would call forth long-forgotten memories,

the skin on your fingertips – so alive, so electric –

singing a song you swear you’ve heard somewhere once before,

even if you don’t seem to know any of those words.

Perhaps some part of you would smile a knowing little smile,

throw back your throat

and howl.

Perhaps then, we’d feel at home in our bodies instead of constantly warring against them.

Perhaps then, the dust of the earth would rise.

Yes! Thank you, I love this ❤️